Books

Magazines

Art

Editions

Multimedia

Allied Publishers

Authors

Style

Perla Medley

Posters & Postcards

Antiquarian

Publication about one of the most interesting contemporary Czech artists, painters, and performers. Jiří Surůvka in full-color with an English insert and large poster. Works include The Dogs of War, The Age of Plastic, Böhmischer Dorf, Venus’s Fly-trap and everything introduced by Jana and Jiří Ševčik on the meaning of the artistic personality of Surůvka. The latest issue of Umělec with the purchase of the catalogue.

Lecture by Jana and Jiří Ševčík on Jiří Surůvka

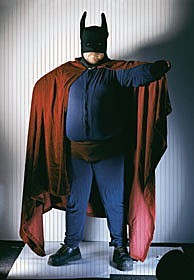

Jiří Surůvka’s mentality is the mentality of a performer who is deeply involved in the art of life. His performances are realistic, brutal and very different from the tradition of 1960’s and 1970’s. While at that time, performances aimed for an alteration and had an atmosphere of initiation with the artist taking on a role of a shaman, recent performances on the emerging Ostrava scene of which Surůvka is an active member do not have the same ritualistic elements– they continue in the older tradition of militant irony. They are more tongue-in-cheek, aggressive and they take on a socially critical and morally critical role. Surůvka does not play a shaman any more today but instead his role is that of a political clown in a reinvented dada cabaret ”The Lozinski Support Band” which he created together with his cousin Petr Lysáček and other artists. His role of a clown has already been shaping up in the years of what was called the real socialism. He invented an absurd yet logical theory on ”the complementary world” that enabled him to accept reality of that period in the following sense: ”... our reality is a complement to the ideal and as such it has a right to exist. Similarly a theory saying that Adolf Hitler significantly contributed to the successful course of the Second World War may hold its ground.” In addition to his improvised performances, Surůvka regularly organizes some sort of dada-body-art in public space, in the streets, and in supermarkets. He chases us out from galleries and artistic ghettos to the streets to see a cabaret with a schoolgirl, Batman and Adolf Hitler singing together.

Surůvka comes out of the environment of emancipated outsiders and amateurs in the devastated city of Ostrava, taking advantage of all its positive features. A strong subculture lives on extremes. On extremes of decentralized intellectuals, heretics, anarchists and libertine dilettantes. This environment lacks the violence of tradition and esthetics, fear of loosing continuity. On the other hand, one may have a light-hearted conversation with the evil (as a complement to the moral ideal). The Ostrava scene includes the last remains of subcultural bohemian people and is typical for its carnival-like elements such as the Malamut international performance meeting during which Surůvka, dressed as Batman, sets off to the streets with his accomplices – apocalyptic knights armed with chainsaws, mowers and helmets. Having taken place four times already, Malamut went unnoticed by art critics despite its importance for the country. The festival’s performances go beyond boundaries of professional cultural institutions and naturally infiltrate social life. They, indeed, have a character of a lived presence. Confronting common urban life, their participants are running a risk of being misunderstood. There, however, is no other way as the peripheral art scene lacks the safety net of professional institutions and the upholstered asylum of galleries. Ostrava artist is not being blocked by any mediators and has to have a ”primitive” relation to reality. The artist has to be anti-psychological and has to be able to naturally evoke even destructive atmosphere. The performances, however, do not follow the old well-arranged and precisely prepared scenarios. The classic performance is undermined and the artist, with his provisional philosophy and provisional art, shows himself in the role of a representative of power both in terms of society and arts. The esthetics of morale is turned inside out. Instead of a shaman, a clown walks up on stage showing that the most commonplace bodily act may mean that our lives are not secured. It is a very effective therapy in today’s political spectacle which has already been suggested by the dadaists: ”the moment we sit down on a chair means that we put our lives in danger”.

His performance and ”complementary strategy” also form background for Surůvka’s paintings, installations and objects. They are based on the same extremes and start up ironic polemic with time and its cynical foundations. Just with two or three paintings, Surůvka is able to show the real state of affairs. His image repertory ironically paraphrases (and embodies) all representatives of power – aggressive militarism, politics, the state, the nation, arts, pop-culture, and sex. Surůvka is a moralist who seemingly accepts the situation with his self-ironizing pose and confuses viewers by suggesting that there may be two ways of looking at things. He questions a principle of power and goes on living and laughing happily. In the Czech art scene, Surůvka represents a shift of the art’s and the artist’s social function away from 1960’s and 1970’s culture and from the postmodern way of the 1980’s. It is a shift that has been brought about by certain sickness with culture and politics. Even from the center’s esthetic viewpoint, Surůvka is perceived (complete with his local scene) as a moral alternative and positive negation.

Pages 8 and 9, Warlords I-VI, 1996-97, acrylic on canvas, 100 x 70 cm*Pages 10 and 11, Left: Warlords I-VI, 1996-97, acrylic on canvas, 100 x 70 cm and Drunk driver, acrylic on oil paint by S. Novotná, 90 x 100 cm*Batman