Books

Magazines

Artwork

Editions

Multimedia

Allied Publishers

Authors

Style

Perla Medley

Posters & Postcards

Antiquarian

English and Czech

Dorka of Pláně,

Her Magazines and Now Her Catalogues

Jiří Ptáček

I

To have a catalog of one’s own is one of the vain desires of visual artists. When a catalogue is released, an artist rejoices: he has been noticed, classified, categorized – unequivocally catalogized. His rejoicing is not a matter of habit; the catalog is the confirmation of his expanding tendency and identity, the same kind of fetish that Narcissus discovered for himself in his pond. “This then, is me. Here I am, and this is who I am. My works will disperse, but the catalog shall remain.”

II

Similarly, a business company in the era of advanced capitalism absolutely has to have its catalog. With the dream of profit and the terror of competition, it focuses on revealing all the weaknesses of the potential customer, using the catalogue to ingratiate itself to the customer’s taste. A catalogue does not ostensibly bother the customer, but does attack him subliminally, creating the illusion that both parties share a common interest: the customer’s own well-being. The happy customer (no longer a potential one) eventually puts the catalogue aside – when it no longer offers anything the customer does not already have by this time. And if a catalogue should fall into one’s hands that fails to address one’s weaknesses, the whole process can be even faster: it simply goes to the recycle bin directly. Companies are aware of the transitory quality of their publications, and resignedly prepare new editions. Thus, while an artist’s catalogue as a rule has the potentiality to participate in historical and social “immortality”, a commercial catalogue is happy to address the next afternoon of shopping. We have one word for both of them, but we mean different things.

III

Vít Soukup has his first large art catalogue, and it features canvases depicting a commercial catalogue. What made him dedicate his first “dab at immortality” to the ephemeral world of “great bargains and discounts”? I have the suggestion of an answer ready, and if I were delivering a speech, I would introduce it with a dramatic pause. But as it is, I will divert the reader’s attention, and leave the answer for the ending. To those who are reluctant to follow the precarious arc of my narration, the cracking and crumbling of the text, I recommend them to skip the following and go straight to section VII. It will save them the long-windedness and their time – that is to say money.

IV

The latitude is 48° 46’ 39“ and the longitude is 14° 25’ 7“ in the village of Dolní Pláně. Wedged between the wooded hills Horní Háj, Hůra, Kraví Hora and Poluška it is like any other place in the hilly South Bohemian borderlands. One may take the northeast direction towards Český Krumlov, or linger in the neighboring valley, which stretches to Velešín and to the pilgrim village St. John upon Malše, poised atop the feminine-shaped knoll. At the beginning of the 1970s, Soukup’s parents bought a cottage in Dolní Pláně. They chose to spend the summers away from the city, like tens of thousands of other Czechoslovaks of their time. Vít Soukup would spend his summer vacations here, slowly evolving into a painter, filmmaker and writer. Today one would hardly recognize that he is not a local. At the village dances in the neighboring village of Věžovatá Pláň, or in nearby Zubčice and Markvartice the talk sometimes turns his way; he is spoken of as a decent boy, the strange painterly fellow, the recovered alcoholic. That his good reputation does not limit itself to the artistic circles of Prague is something they are only beginning to discover. As is the world that Soukup takes into account in his work. Surprisingly, they are learning about their own universe, of the village, of the periphery, of their outsider status.

V

Vít Soukup’s oeuvre can be characterized by one constant feature: the bond of botched handicraft and failure in the life in the name of an intellectual commentary on lifestyle and aesthetic values. His diction is a mixture of irony and compassion. Among other examples of this attitude we might first cite Soukup’s fumetto series Radka Likes to Date / Radka ráda randí, created for Umělec magazine between 1998-99. In this a young artist named Radka is going through both a personal and a professional crisis, and moves into the “heart of the Novohradské Hory” where, next to her simpleminded but noble and refined boyfriend Honza, she “realizes” the simplicity and the importance of the value of love.1 What is significant here: the romance is fulfilled through a subversive satire of clichés of the artistic milieu, of which Soukup himself is a part. Another example is the series of wooden objects from Soukup’s country garden in Dolní Pláně. These were unexpectedly included in Soukup’s large retrospective A Posthumous Exhibition / Posmrtná výstava (2003). Soukup had the rickety wooden vehicles transported to the House of Arts in Zlín, and there “reconstructed” them. He monumentalized this childish work of arte povera into a powerful artifact ironically glorifying exhibitions. Soukup often applies a similar “aggrandization” in his painting. In his series Techno (1999) he reconstructed illustrations from didactic magazines for teenagers into gigantic oil paintings that oscillated between the style of Mark Rothko and the sensibility of Jeff Koons. Quotes from the history of art were not alien to him, and yet still could not mask the fact that it is not merely a meditation on painting or global pop populism, but a damnable humanistic intrusion into the everyday life of our prefabricated, middle/class, Bakelite, “do it yourself” culture. Soukup likes to create the Czech variation of Pop Art – concentrating on consumer products, but those that are symptomatic for the local dynamic of social changes. He will concentrate precisely on those reproductions that have faded and turned into cheap prints; they demonstrate all the more clearly how cheaply produced is the chimera of consumerism and technological progress. He concentrates on objects that bear evidence that both our former and present ideals do not exceed the minuscule proportions of our Czech Valley, and yet are capable of looming above the horizon of our minds, becoming our fate. Soukup consistently paints entirely in oils and with respect to the model, thus becoming a follower of similarly faded, model-enslaved and baroque second-rate artists (and even the few first-rate ones) whose paintings still crowd our minor churches and chapels. We could go on citing examples, the lost pastel paintings based on Rumcajs, or the several series of small oil paintings on roughly cut wooden blocks featuring motifs of regional and normalization-era periodicals. We would then arrive to the series Dorka 2 (2003), in which Soukup again searched for the abstract aesthetic of modernist painting (this time aided by knitting magazines inherited from his mother) but eventually could not resist the branches of the Dolní Pláně conifers, and the petite paws of a local cat. But in fact that leads us to repeat, a propos of everything again and again: we are the world’s outsiders, and it is worse to deny this than to admit it. Our experience grows out of the polyphony of theses, discourses, and ideals as well as from the parallel “ornament” of our personal preferences, irresponsibility and sentiments. Ideals sell out, and give way to the “little joys”, emotional instability as well as the conditions of our social macrocosms. And we will be able to say that this is bad or good only with our eyes closed. 2

VI

We must not ignore the fact that Soukup’s work has features of personal mythology and spirituality. However, a more significant factor is the system of codes of “realization of shared experience” that the chosen sources of inspiration manifest. Via periodicals such as ABC, Květy, Dorka, the daily Český Krumlov Pages, or cheap westerns, Soukup does not open gates towards a nostalgic sentiment towards the 1980s and to local comics3, but to the experiences that we have in common and that we will never manage to shake off. The advantages granted to Czech artists by the unified and uniform history of our country after the Second World War and the relatively recent post-socialist diversification are currently appreciated by a wide range of Czech artists.4 Vít Soukup does not imply that we should, as a matter of principle, shudder with horror at our limitations, nor to go all willy-nilly regarding our inalienable identity and authenticity. Soukup’s canvases, like his films, merely state the paradox of our balancing act on the twin crutches of mind and body. Managed, of course, with a great amount of nuanced taunting of one against the other. If he does so “in his own name, in the name of his fallen spirit and in the name of his time limited body, for himself as painter and filmmaker”, he gains an indisputable alibi in the sense that he does not exclude himself from this system. For in truth, an attitude so frequently repeated cannot be an accompaniment of some essentially based obsession.

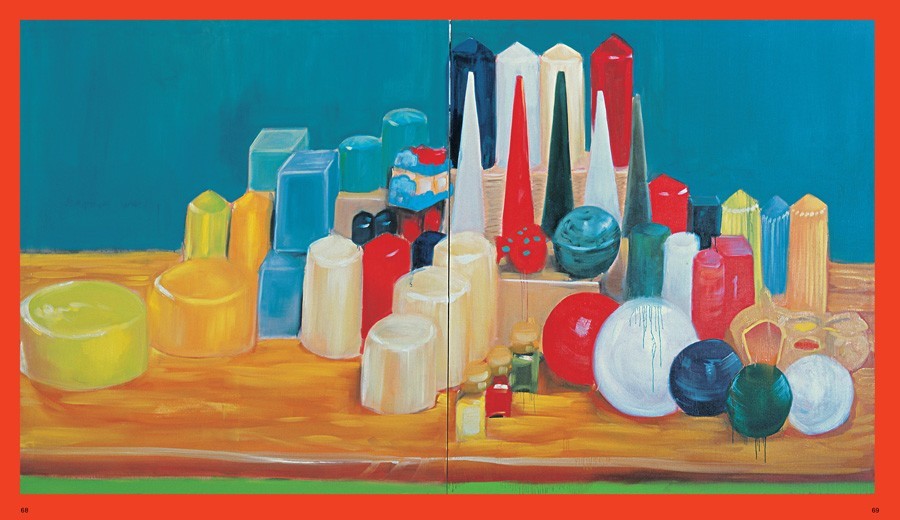

VII

The most recent series Catalogue is characterized more than others by a certain impetuosity. Soukup has never worked with such frantic haste. Colors blur more than ever, and unsolidified they yield themselves to new interpretations. Objects represented here, with few exceptions, do not appear to be based on photographs. But these exceptions only demonstrate anew Soukup’s reluctance to work on solitaires. The series, or the cycle, is his medium. Implying that a story is running through the paintings, asserting that the subject matter has not been chosen randomly, but with the awareness of the task to communicate and persuade the viewer of the significance of the theme. The paintings in Catalogue capture a choice of goods we may encounter in any broadsheet of the OBI domestic utensils chain. Consumer goods lacking in quality, but overpowering through sheer volume. Vít Soukup records this as if peripherally, in passing. The colorful patterns and compositions of the objects often serve as the pretext for losing control over the physical reality of these objects – this is the case here in several instances. For example, a flower breaks free from the wallpaper – or is it fabric? – thus emancipating itself and blossoming as the illusion of a natural plant. Again, it is in the exceptions where Soukup conclusively illuminates that we are not in a hypermarket, but perhaps at our mailbox, leafing through fliers and assorted junk mail. We are implicated in the situation of people who are showered with kilotons of an explosive mixture of discounts and bargains. Who are these imaginary people? Perhaps I will not stray too far from truth by saying that, at least sometimes, all of us are. Commercial catalogues are sometimes thrown straight away, and sometimes kept until the next shopping expedition. But sometimes we stare agape at their lurid clowning, for we understand it so well. It is inherent to us… we must shop, since, due to some unfathomable instinct we still want to. Vít Soukup has sacrificed his first art catalogue to the song of its ephemeral catalogue sister. Still, upon the foam of its singing organ, there now and then glitters the reflection of our longing for beauty, comfort and happiness, which resonates in “our” painter, both warming the heart and embarrassing us.

Page 2*Page 4 and 5*Page 6 and 7*Page 10 and 11*Page 20 and 21*Page 22 and 23*Page 28 and 29*Page 32 and 33*Page 36 and 37*Page 40 and 41*Page 42 and 43*Page 46 and 47*Page 52 and 53*Page 54 and 55*Page 58 and 59*Page 64 and 65*Page 66 and 67*Page 68 and 69